|

The first underglaze blue wares seen in England were Chinese porcelains with painted decoration. Chinese porcelain was viewed as the ceramic ideal - fine, white, and translucent, and often with exotic imagery painted in blue. By the late seventeenth century “china mania” was the fashionable obsession. In the early eighteenth century, imports by the East India Company rose to meet demand. By the middle of the century English porcelain manufacture was under way, so “china” of all kinds became increasingly available to the wealthy royal and noble classes. Inspired by the painted porcelains of China, the earliest decorations in blue on English ceramics are hand painted. But, to produce complex designs and to create tea and table services with consistent patterns, the manufacturers needed to develop a printing process. The first underglaze blue wares seen in England were Chinese porcelains with painted decoration. Chinese porcelain was viewed as the ceramic ideal - fine, white, and translucent, and often with exotic imagery painted in blue. By the late seventeenth century “china mania” was the fashionable obsession. In the early eighteenth century, imports by the East India Company rose to meet demand. By the middle of the century English porcelain manufacture was under way, so “china” of all kinds became increasingly available to the wealthy royal and noble classes. Inspired by the painted porcelains of China, the earliest decorations in blue on English ceramics are hand painted. But, to produce complex designs and to create tea and table services with consistent patterns, the manufacturers needed to develop a printing process.

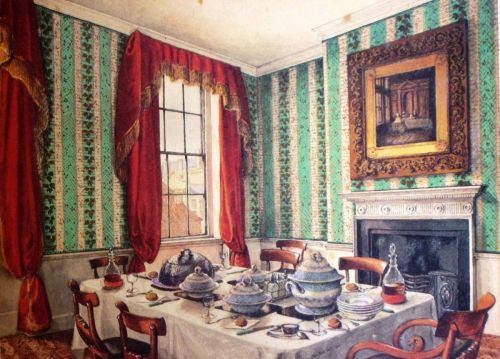

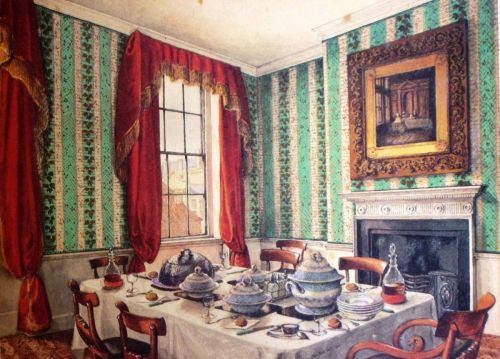

In the mid 1750s, under the direction of Richard and Josiah Holdship and with the artistic skills of Robert Hancock, the Worcester porcelain company began to print over the glaze and, more importantly for the history of Spode, under the glaze in blue. Soon the techniques spread to other porcelain factories and each company fought to secure a share of the lucrative blue and white market. and with the artistic skills of Robert Hancock, the Worcester porcelain company began to print over the glaze and, more importantly for the history of Spode, under the glaze in blue. Soon the techniques spread to other porcelain factories and each company fought to secure a share of the lucrative blue and white market. Social and economic changes that took place in eighteenth century England saw a growing number of middle class families who aspired to a more sophisticated lifestyle. They wanted to emulate the wealthy in setting a grand table but they could not afford porcelain. Identifying a niche market, Spode capitalized on the appeal of highly desirable blue

decorated porcelains by creating less expensive versions in blue printed earthenware. As skilled workers began to move between factories, Josiah Spode I engaged the services of an experienced engraver to help him develop patterns for printing on earthenware. By 1785, and possibly as early as 1784, the combination of technology and artistic talent had Spode producing the first underglaze blue-printed earthenware.

The first underglaze blue wares seen in England were Chinese porcelains with painted decoration. Chinese porcelain was viewed as the ceramic ideal - fine, white, and translucent, and often with exotic imagery painted in blue. By the late seventeenth century “china mania” was the fashionable obsession. In the early eighteenth century imports by the East India Company rose to meet demand. By the middle of the century English porcelain manufacture was under way, so “china” of all kinds became increasingly available to the wealthy royal and noble classes. Inspired by the painted porcelains of China, the earliest decorations in blue on English ceramics are hand painted. But, to produce complex designs and to create tea and table services with consistent patterns, the manufacturers needed to develop a printing process. In the mid 1750s, under the direction of Richard and Josiah Holdship and with the artistic skills of Robert Hancock, the Worcester porcelain company began to print over the glaze and, more importantly for the history of Spode, under the glaze in blue. Soon the techniques spread to other porcelain factories and each company fought to secure a share of the lucrative blue and white market. and with the artistic skills of Robert Hancock, the Worcester porcelain company began to print over the glaze and, more importantly for the history of Spode, under the glaze in blue. Soon the techniques spread to other porcelain factories and each company fought to secure a share of the lucrative blue and white market. Social and economic changes that took place in eighteenth century England saw a growing number of middle class families who aspired to a more sophisticated lifestyle. They wanted to emulate the wealthy in setting a grand table but they could not afford porcelain. Identifying a niche market, Spode capitalized on the appeal of highly desirable blue

decorated porcelains by creating less expensive versions in blue printed earthenware. As skilled workers began to move between factories, Josiah Spode I engaged the services of an experienced engraver to help him develop patterns for printing on earthenware. By 1785, and possibly as early as 1784, the combination of technology and artistic talent had Spode producing the first underglaze blue-printed earthenware. |

|

The first underglaze blue wares seen in England were Chinese porcelains with painted decoration. Chinese porcelain was viewed as the ceramic ideal - fine, white, and translucent, and often with exotic imagery painted in blue. By the late seventeenth century “china mania” was the fashionable obsession. In the early eighteenth century, imports by the East India Company rose to meet demand. By the middle of the century English porcelain manufacture was under way, so “china” of all kinds became increasingly available to the wealthy royal and noble classes. Inspired by the painted porcelains of China, the earliest decorations in blue on English ceramics are hand painted. But, to produce complex designs and to create tea and table services with consistent patterns, the manufacturers needed to develop a printing process.

The first underglaze blue wares seen in England were Chinese porcelains with painted decoration. Chinese porcelain was viewed as the ceramic ideal - fine, white, and translucent, and often with exotic imagery painted in blue. By the late seventeenth century “china mania” was the fashionable obsession. In the early eighteenth century, imports by the East India Company rose to meet demand. By the middle of the century English porcelain manufacture was under way, so “china” of all kinds became increasingly available to the wealthy royal and noble classes. Inspired by the painted porcelains of China, the earliest decorations in blue on English ceramics are hand painted. But, to produce complex designs and to create tea and table services with consistent patterns, the manufacturers needed to develop a printing process.